Vamar History from Florida DHR on Vimeo.

Click the play button above to view a brief history of the single screw steamer Vamar. View a transcript (PDF 20KB) of this video.

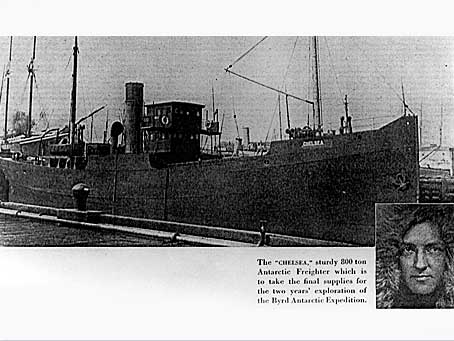

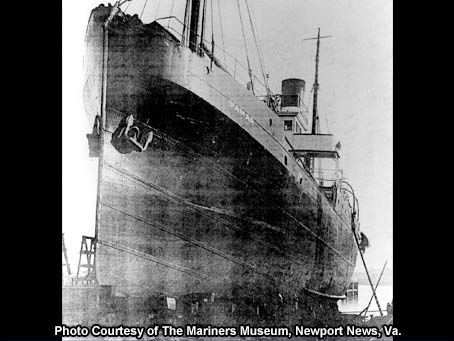

The vessel that sank off Mexico Beach was built in 1919 by Smiths Dock Company of Middleboro, England. Originally christened Kilmarnock, the ship was built for the British Admiralty as part of the Kil class of patrol gun boats. Recorded dimensions were 170 feet in length, 30 feet in beam, a depth of hold of 16 feet, and 598 gross tons. The hull was of steel construction with triple expansion steam engines for propulsion. In the 1920s Kilmarnock was sold to a private firm and renamed Chelsea.

In July 1928, Rear-Admiral Richard E. Byrd, USN, acquired Chelsea as one of two support vessels that would carry his first expedition to Antarctica. Byrd planned to construct a polar base from which he hoped to make the first aerial fly-over of the South Pole. He purchased the small freighter for $34,000 from the government's "rumrunner's row" of vessels confiscated for smuggling liquor. Byrd chose Chelsea because she was cheap and available; otherwise, he confessed, she had little to recommend her. The primary expedition ship, City of New York, was a sailing ship with a wooden hull ideal for advancing through polar ice packs; however, her hold was too small for the crates containing the airplanes that were to fly over the South Pole. Chelsea's hold, on the other hand, contained two large cargo areas with a combined capacity of 800 tons.

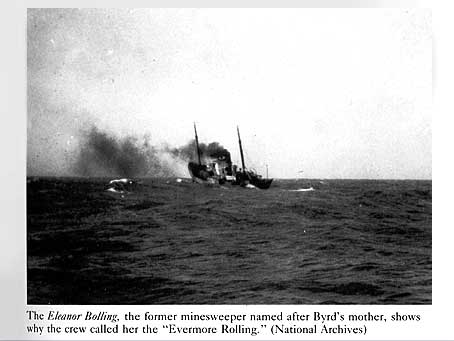

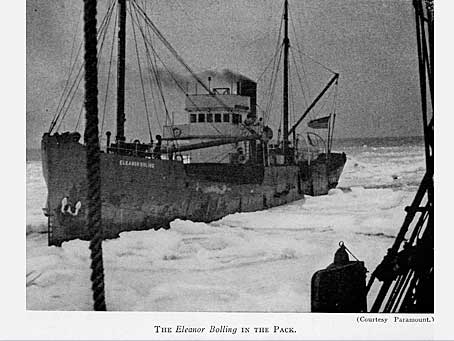

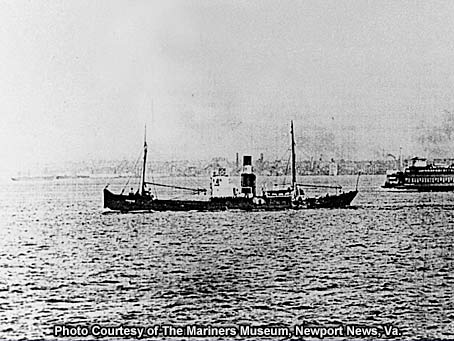

Byrd renamed the steamer Eleanor Bolling after his mother, Eleanor Bolling Byrd. The vessel underwent some $76,000 in repairs and upgrades at the Todd Shipyard in England. One of the most important upgrades was reinforcement of the bow area to withstand Antarctic ice; Bolling subsequently became the first metal-hulled vessel to be used in Antarctic waters. The ship proved to be sturdy but not especially stable; her crew, after encountering rough waves in the southern ocean, nicknamed her "Evermore Rolling." Eleanor Bolling made several voyages between Antarctica and New Zealand before the expedition was completed in 1930. On June 19, 1930, she and City of New York sailed into New York harbor amid enormous fanfare. Later that year, Byrd sold the vessel to an Arctic sealing company for $15,000, considering her unseaworthy for a second Antarctic expedition.

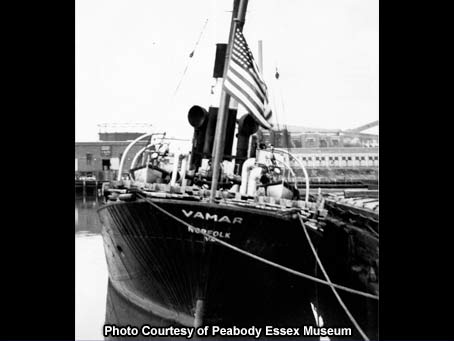

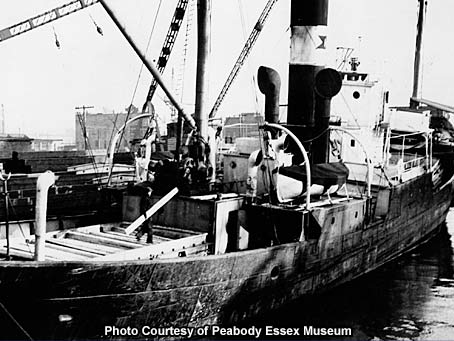

In 1933, the ship was purchased by Vamar Shipping Company and renamed Vamar. By 1942, Vamar was owned by Bolivar-Atlantic Navigation Company under Panamanian registry and used as a tramp freighter. Various Coast Guard reports indicate the steamer was falling into disrepair, with her equipment in poor condition and no radio operator onboard. On March 19, 1942, Vamar entered Port St. Joe with a crew of 18 (Yugoslavian, Cuban, and Spanish) to take on a load of lumber for Cuba. On March 21, Vamar left the dock and headed through the channel toward the Gulf of Mexico. According to an incident report given by Harbor Pilot J. Melvin Beck, who was aboard the ship when it sank, the steamer was overloaded and seemed to be top-heavy from too much cargo stowed on the deck. As Mr. Beck guided Vamar through the channel, she listed to port and began to go down by the stern. After managing to get the sinking freighter out of the channel, Mr. Beck and all the crew abandoned the ship and returned safely to Port St. Joe.

For several weeks, Vamar's captain and crew remained in Port St. Joe and apparently aroused the townspeople's suspicion by their conduct. The crew's behavior together with war-time concerns for security caused the Coast Guard to initiate an investigation into the sinking. Two Coast Guard investigators were sent to Port St. Joe in May. The investigators questioned salvage divers working to raise the wreck, as well as many people in the town who had knowledge of the sinking incident and the crew's subsequent activities. Some of those who were questioned suggested that the ship had intentionally been sunk by saboteurs to block the channel and provided information about the dubious circumstances surrounding the sinking. For example, when Vamar went down she had already navigated two sharp turns in the channel and was on a straightaway in calm water. Additionally, Mr. Beck told Vamar's captain she was overloaded and top-heavy but his advice to shift her cargo was ignored.

Although the investigators noted the concerns of the local people and followed leads on the questionable behavior of the crew and rumors of holes in Vamar's hull, they could not find enough evidence to substantiate the suspicions. The exact reason why Vamar sank has never been determined, although overloading and shifting cargo generally are blamed. Nevertheless, the specter of foreign war-time sabotage still looms over the shipwreck.

In 2002, Vamar was nominated to become Florida's ninth Underwater Archaeological Preserve. The site was recorded and the ship's history researched by State archaeologists and the Marine Archaeological Research & Conservation Reporting (MARC) team. The Vamar Preserve was dedicated, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, in 2004.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger versions of these historical images of Vamar.

{caption}