Tarpon History from Florida DHR on Vimeo.

Click the play button above to view a brief history of the single screw steamer SS Tarpon. View a transcript (PDF 20KB) of this video.

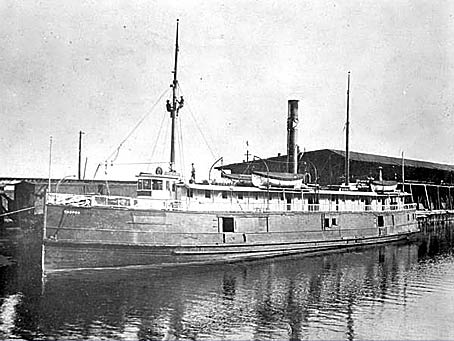

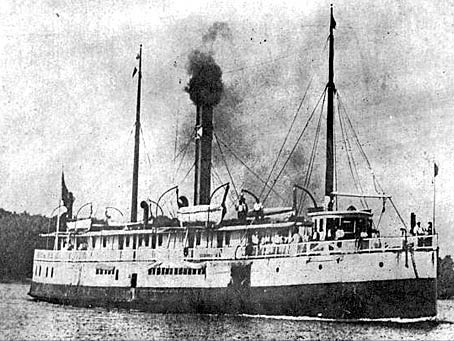

The twin-screwed freight and passenger steamer Tarpon was constructed in 1887 at Wilmington, Delaware. Originally named Naugatuck, the iron-hulled vessel measured 130 feet in length, 26 feet in beam, with 8 feet depth of hold. She was powered by twin compound fore-and-aft steam engines driving twin iron propellers.

Two years after she was built, Naugatuck’s owners sold her to Henry Plant, whose railroad empire terminating at Tampa, Florida, was one of the largest conglomerates in the United States. In 1891, she was sent back to her builders, who lengthened the vessel by 30 feet. Renamed Tarpon, she returned to her Florida career, and may have been one of the dozens of Plant vessels used to transport troops and supplies to and from Cuba during the Spanish-American War. In 1902, the vessel was sold to the newly incorporated Pensacola, St. Andrews & Gulf Steamship Co., and was put in the charge of Captain Willis G. Barrow.

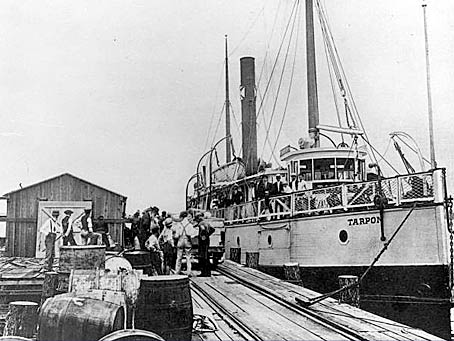

Beginning in 1903, Tarpon and her master became famous along the northern Gulf Coast, making weekly runs between the ports of Mobile, Pensacola, St. Andrew Bay (Panama City), Apalachicola, and Carrabelle. With few paved roads or bridges, commerce and communication between coastal communities was almost totally dependent on water-borne traffic. Barrow and Tarpon developed a reputation for reliability and dependability, transporting passengers and essential supplies while maintaining a strict schedule regardless of weather. The captain often was quoted as claiming that “God makes the weather, and I make the trip.” Despite storms, hurricanes, groundings, and fires, Tarpon continued her weekly schedule between six ports year in and year out. In December 1922, Barrow celebrated 20 years as master of Tarpon by completing their 1,000th voyage to St. Andrew Bay, having missed only one trip on account of bad weather. An admiring local press estimated that the steamer had traveled a distance of 700,000 miles – equal to 28 times around the earth. By January 1933, Barrow marked his 30th year as Tarpon’s skipper, having completed 1,500 voyages.

Although weather forcasters predicted calm seas, the wind had freshened by the time Barrow retired for the night to his cabin, placing second mate William Russell at the helm. At 2 a.m., chief engineer Lloyd Mattair began to have difficulties keeping water pumped from the bilges due to a leak in the bow that was steadily increasing in rough seas. The ship began to list to port as the men worked the pumps. First mate L.E. Danford put the helm into the oncoming seas, and ordered barrels of flour jettisoned from the port side to counter the list. When the steamer returned to an even keel, she was put back on course. In his cabin, Capt. Barrow remained confident of his ship despite the increasing weather. Just before dawn, the wind reached gale force, and the pounding seas began to pour through Tarpon’s wooden bulkheads, causing her to list to starboard. Roustabouts were sent below again to jettison more cargo, but the crew began to realize that the ship could not be righted. Less than 10 miles from shore, Tarpon had begun to sink. When Barrow finally gave the order to abandon ship, the vessel already had settled into the sea by the stern. Tarpon carried no radio, and no distress flares were fired.

The crew frantically donned life jackets and tried to launch the four lifeboats. Most of those below remained trapped as the ship plunged beneath the waves. Only one boat was freed, but it capsized, drowning the cook’s wife. Those on deck were washed away, including Tarpon’s 81-year-old captain, who succumbed around noon that day. Amidst debris in the water, survivors floated alongside their drowned shipmates. As the weather cleared, oiler Adley Baker sighted land in the distance and decided to swim toward it. He finally staggered ashore west of Panama City, after spending 25 hours in the water. A passing motorist picked Baker up and drove him to Panama City, where news of Tarpon’s sinking quickly spread by word of mouth and by telegraph. The Coast Guard dispatched a search plane and two cutters to the scene to look for survivors; of those rescued, some had been in the water over 30 hours. Eighteen people are believed to have lost their lives; some, including the roustabouts trapped in the cargo hold, were never identified.

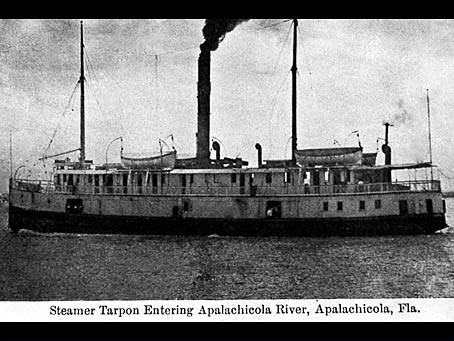

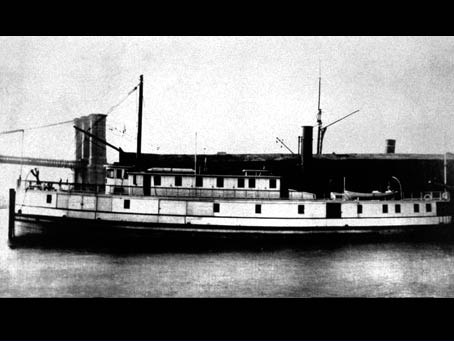

Click the thumbnails below to view larger versions of these historical images of SS Tarpon.

{caption}